Rembrandt is a mis-understood artist, but not in the conventional sense. The people of his own time understood him rather well. . .it is subsequent generations who suffer from mis-information about his origins and his experiences. Although his history has recently emerged from the inaccuracies that abounded in the mid-20th century, it doesn't hurt to review the facts in light of the still-viewed movie, "Rembrandt" produced in London in the 1930's, and the possible conclusion that being an "old master" takes you off of the cutting edge of the current art scene.

Walter Wallace gives an excellent overview of Rembrandt's actual history in his book, "The World of Rembrandt."

("The Legend and the Man," in The World of Rembrandt: 1606-1669 ((Time-Life Library of Art)), Walter Wallace, New York, 1968, pp. 17-25)

Wallace expresses regret that the myth of a struggling, uneducated artist, an only child despised by those around him, traveling around the world only to find ruin, persists in the face of many scholarly attempts to set the record straight. Despite the popularity of the London movie staring Charles Laughton and Gertrude Lawrence, Rembrandt's reality was quite different.

There are recorded documents stating that Rembrandt's mother, upon her death, when the artist was 34 years old, left an estate of 10,000 florins in a time when a typical weaver might make about 1400 florins a year. So much for poverty.

His father was a miller, and in the liberated climate of the United Provinces, recently freed from Catholic Spain, it was not unthinkable that a miller's son could become a professional. So much for peasantry.

Other records tell us that Rembrandt was the eighth of nine children. So much for being an only child.

While there are a few records of his siblings, Rembrandt was the only one that was sent to polish his skills. At the age of seven, Wallace tells us, he commenced a seven-year regimen that was to include:

". . . the reading of Cicero, Terence, Virgil, Ovid, Horace, Caesar, Sallust, Livy and Aesop. The students conversed in Latin, and Rembrandt became accustomed to the Latin form of his own name, Rembrantus Harmensis Leydensis (Rembrandt the son of Harmen of Leiden). It was for this reason that he signed his early works with the monogram, RHL. Rembrandt not only passed the course, but later recalled it in detail; his historical and mythological paintings reflect meticulous attention to the texts on which they were based."

When he turned to art, at the age of fourteen, he was apprenticed first to an unknown artist, then to Jacob Van Swanenburgh, where he learned the basics of painting, drawing and etching.

After three years, he was sent 30 miles away to Amsterdam to study under Pieter Lastman, a painter who had studied in Rome. Lastman painted historical scenes using vibrant color to depict the subjects accepted by the traditional norms of the Catholic Church (although Catholicism was increasingly driven underground in the United Provinces). Lastman himself had been greatly influenced by Caravaggio, who used light and shadow to produce emotion and mystery in painting. Lastman also studied Adam Elsheimer when he was in Rome. Elsheimer was a German painter who used the Caravaggio technique to produce smaller detailed works.

After a short time with Lastman, Rembrandt, before the age of 20, established himself in his home town of Leiden as an independent master. It is very unlikely that he ever left his native country, although he did move to the larger city of Amsterdam, where he absorbed all the culture of a thriving artist community, and applied his education to the execution of his work.

So much for ignorance and wandering around Europe.

It is true, however, that Rembrandt experienced bankruptcy, but it wasn't for lack of customers or reputation regarding his competence. His "Night Watch" was fully appreciated by the public and honored by its commissioner. The Prince of Orange paid him an even greater sum a few years later for other artistic work. Rembrandt, it seems, had a problem managing his money, even though he had a rich wife; he found it difficult to resist investment in art, and he bought a bigger house than he could afford. And even though he produced many portraits of citizens and landscapes, he refused to totally succumb to "popular" values. He had some troubles with his in-laws, and his female servants, after his wife's death. These were the real reasons for his bankruptcy.

Wallace gives us a good picture of this era. The United Provinces, sometimes referred to as "Holland," had won its independence from Spain and the Catholic Church during Rembrandt's early childhood. Although the generous commissions from the Catholic Church were no longer available to artists, the population of this newly-liberated nation was hungry for art, and defined their own standards. They liked visual realism, and since it was often the tradesmen and artisans that were the buyers, they wanted pictures of their own families and everyday circumstances. There were thousands of artists in this climate that were producing portraits and still life scenes for popular consumption at an astounding rate, which was one of the reasons that few of the artists died rich men.

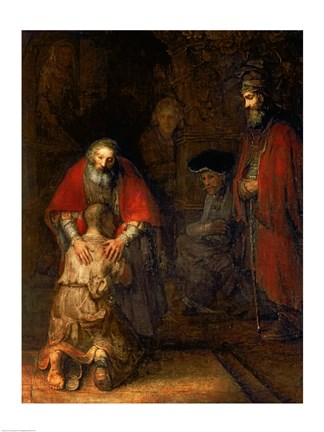

The traditional custodian of "art" (specifically, the Church of Rome) demanded that history and religion be the highest and best use of artistic talent, and Rembrandt never rejected this perspective, always producing historic and religious scenes for the edification of his public. Even in his portrayals of his fellow citizens, his work was never devoid of humanitarian values, and an egalitarian view. As the monied classes created by the House of Orange prospered, they preferred artists who portrayed them in a worldly sense. Rembrandt accepted these commissions, but probably made them think a little more than they would have liked. The foreign exploits of the Dutch were not glorified by their artists, perhaps because the nation's foreign accomplishments included harsh wars waged and debts incurred at the expense of their neighbors' lives and livelihoods.

Rembrandt's first painting master, Jacob Van Swanenburgh, was known for his various examinations of Hell, but Rembrandt eschewed the use of fear, preferring instead to instill an appreciation of man's capacity for development of character and good use of the concept of love and honor. Throughout his works, which include over 2300 paintings, etchings, and drawings, there persists religious and historical references to remind us of the role and capacity of mankind that is present, in his view, in every individual.

"Young Woman with a Broom" which resides in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. is a good example of his powerful reminder that every human soul has dignity. Instead of portraying the child as a defeated servant, she has the light of intelligence in her aspect, and she holds the broom as a musician might hold a cello, with the utilitarian bucket overturned and forgotten.

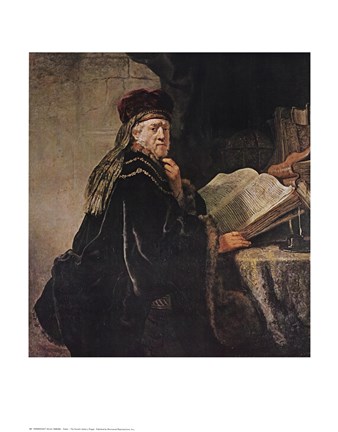

"The Rabbi," a subject that is without parallel for European controversy, condenses all of the issues into the mind, and then the face, of a man as he confronts a visitor.

Rembrandt's reach into our consciousness, and our consciences, continues with his full range of subject matter, from Dutch landscapes to Jesus on the cross to depictions of war to local gentry to Bathsheba reading David's letter. His command of art as a living platform to educate and inspire continues with undiminished power across the centuries.

View our collection of Rembrandt artwork, including the popular "Return of the Prodigal Son" at http://fulcrumgallery.com.'